Murder Of Lord Darnley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The murder of

The murder of

Mary, Queen of Scots visited from Holyroodhouse. Lord Darnley's chamber servant Thomas Nelson mentioned how the queen and Margaret Beaton, Lady Reres would play and sing in the garden at night time.

Early in the morning of 10 February, the house was destroyed by a

Mary, Queen of Scots visited from Holyroodhouse. Lord Darnley's chamber servant Thomas Nelson mentioned how the queen and Margaret Beaton, Lady Reres would play and sing in the garden at night time.

Early in the morning of 10 February, the house was destroyed by a

According to his statement, the next morning the queen's servant Nicolas Hubert, known as French Paris, came to the queen's bedchamber at

According to his statement, the next morning the queen's servant Nicolas Hubert, known as French Paris, came to the queen's bedchamber at

Records of the subsequent trials with statements from the accused and witnesses are an important source of information on the events of February 1567. Most were published in Pitcairn's ''Ancient Criminal Trials in Scotland'' and

Records of the subsequent trials with statements from the accused and witnesses are an important source of information on the events of February 1567. Most were published in Pitcairn's ''Ancient Criminal Trials in Scotland'' and

''Ane Detectioun of the Duings of Marie Quene of Scottes, touchand the murder of hir husband'', (1571)

from

Philological Museum

Pitcairn, Robert, ed., ''Criminal Trials in Scotland'', vol.1 part 2, (1833)

pp. 488–513, original confessions of accessories

Laing, Malcolm, ''History of Scotland with a Preliminary Dissertation on the Participation of Mary, Queen of Scots, in the Murder of Darnley'', vol. 2 (1819)

includes the confessions, the casket letters, and other relevant documents. * * * * * * {{coord, 55.9456, -3.1811, type:landmark_region:GB, display=title Murder in Edinburgh 1567 in Scotland History of Edinburgh Political scandals in Scotland Mary, Queen of Scots Murder in 1567

The murder of

The murder of Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley

Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley (1546 – 10 February 1567), was an English nobleman who was the second husband of Mary, Queen of Scots, and the father of James VI and I, James VI of Scotland and I of England. Through his parents, he had claims to b ...

, second husband of Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of Scot ...

, took place on 10 February 1567 in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

. Darnley's lodgings were destroyed by gunpowder; his body and that of his servant were found nearby, apparently having been strangled rather than killed in the explosion. Suspicion was placed upon Queen Mary and the Earl of Bothwell

Earl of Bothwell was a title that was created twice in the Peerage of Scotland. It was first created for Patrick Hepburn in 1488, and was forfeited in 1567. Subsequently, the earldom was re-created for the 4th Earl's nephew and heir of line, F ...

, whom Mary went on to marry three months after Darnley's murder. Bothwell was indicted for treason and acquitted, but six of his servants and acquaintances were subsequently arrested, tried, and executed for the crime.

Location

Darnley was murdered at the "Old Provost's House" of theKirk o' Field

The Collegiate Church of St Mary in the Fields (commonly known as Kirk o' Field) was a pre-Reformation collegiate church in Edinburgh, Scotland. Likely founded in the 13th century and secularised at the Reformation, the church's site is now covered ...

(formally, St Mary in the Fields). The kirk

Kirk is a Scottish and former Northern English word meaning "church". It is often used specifically of the Church of Scotland. Many place names and personal names are also derived from it.

Basic meaning and etymology

As a common noun, ''kirk' ...

was named for its original situation outside the early town walls, in fields to the south. It was founded by the Augustinians

Augustinians are members of Christian religious orders that follow the Rule of Saint Augustine, written in about 400 AD by Augustine of Hippo. There are two distinct types of Augustinians in Catholic religious orders dating back to the 12th–13 ...

of Holyrood Abbey. First mentioned in 1275, it became a collegiate church In Christianity, a collegiate church is a church where the daily office of worship is maintained by a college of canons: a non-monastic or "secular" community of clergy, organised as a self-governing corporate body, which may be presided over by a ...

before 1511, with a provost, ten prebendaries

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of the ...

and two choristers, and was enclosed within the city with the building of the adjacent Flodden Wall

There have been several town walls around Edinburgh, Scotland, since the 12th century. Some form of wall probably existed from the foundation of the royal burgh in around 1125, though the first building is recorded in the mid-15th century, whe ...

along the south boundary of the church grounds in 1513. The Old Provost's House was built against this wall. The kirk's hospital

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emerge ...

, built against the north boundary of the grounds, succumbed to the Burning of Edinburgh

The Burning of Edinburgh in 1544 by an English sea-borne army was the first major action of the war of the Rough Wooing. A Scottish army observed the landing on 3 May 1544 but did not engage with the English force. The Provost of Edinburgh wa ...

in 1544, the kirk building itself to the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, in 1558. James Hamilton, Duke of Châtellerault

James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Châtellerault, 2nd Earl of Arran ( 1519 – 22 January 1575), was a Scottish nobleman and head of the House of Hamilton. A great-grandson of King James II of Scotland, he was heir presumptive to the Scottish thron ...

, built a mansion on the site of the hospital in around 1552, this became known as the Duke's Lugeing (lodging), or Hamilton House. Kirk o' Field was approximately ten minutes' walk from Holyrood Palace

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly referred to as Holyrood Palace or Holyroodhouse, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinbu ...

, near to the Cowgate

The Cowgate (Scots language, Scots: The Cougait) is a street in Edinburgh, Scotland, located about southeast of Edinburgh Castle, within the city's World Heritage Site. The street is part of the lower level of Edinburgh's Old Town, Edinburgh, ...

.

The lands at Kirk o' Field were later granted to the city by charters from King James VI

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

in 1582, specifically for the foundation of a new university, the Tounis College. Hamilton House was then incorporated as the first major building of the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

. The Old Provost's House was adjacent to the Flodden Wall, and is generally thought to have stood at the current south east corner of the Old College, at the junction between South College Street and South Bridge (the National Museum of Scotland

The National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, Scotland, was formed in 2006 with the merger of the new Museum of Scotland, with collections relating to Scottish antiquities, culture and history, and the adjacent Royal Scottish Museum (opened in ...

is sited to the west of the Old College). During archaeological investigations following the Cowgate fire of 2002, a genealogist raised questions about the exact location of the house.

Darnley's murder

On his return to Edinburgh with Queen Mary early in 1567, Darnley took residence in the Old Provost's lodging, a two-storey house within the church quadrangle. The house was owned by Robert Balfour, whose brother Sir James Balfour was a prominent councillor of Queen Mary. Adjacent was the lodging of James Hamilton, Duke of Châtellerault. At first Darnley's household thought he would be accommodated in the Hamilton Lodging. Mary, Queen of Scots visited from Holyroodhouse. Lord Darnley's chamber servant Thomas Nelson mentioned how the queen and Margaret Beaton, Lady Reres would play and sing in the garden at night time.

Early in the morning of 10 February, the house was destroyed by a

Mary, Queen of Scots visited from Holyroodhouse. Lord Darnley's chamber servant Thomas Nelson mentioned how the queen and Margaret Beaton, Lady Reres would play and sing in the garden at night time.

Early in the morning of 10 February, the house was destroyed by a gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). ...

explosion. Queen Mary was at Holyrood attending the wedding celebration of Bastian Pagez

Bastian Pagez was a French servant and musician at the court of Mary, Queen of Scots. He devised part of the entertainment at the baptism of Prince James at Stirling Castle in 1566. When Mary was exiled in England, Bastian and his family continu ...

. Darnley's father, the Earl of Lennox

The Earl or Mormaer of Lennox was the ruler of the region of the Lennox in western Scotland. It was first created in the 12th century for David of Scotland, Earl of Huntingdon and later held by the Stewart dynasty.

Ancient earls

The first earl ...

later produced a narrative of events which says that some witnesses said Mary was dressed in men's clothing on that night, "which apparel she loved oftentimes to be in, in dancings secretly with the King her husband, and going in masks by night through the street".

The partially clothed bodies of Darnley and his servant were found in a nearby orchard, apparently either smothered or strangled but unharmed by the explosion. Another servant was killed in the house by the explosion, which it was said had such "a force and vehemency, that of the haill ludgeing, walles and uthir, their is na thing left unruinated and doung in drosse to the verie ground stane", (a force and vehemency, that of the whole lodgings, walls and other, there is nothing left which is not ruined and struck down in fragments to the very foundation stone).

Three witnesses made sworn statements on the following day. Barbara Mertine said she was looking out of the window of her house in Friar's Wynd, and heard 13 men go through the Friar Gate into Cowgate and up Friar's Wynd. Then she heard the explosion, the "craik", and 11 more men went by. She shouted after them that they were traitors after an "evill turn." May Crokat lived opposite Mertine, under the Master of Maxwell's lodging. Crokat was in bed with her twins and heard the explosion. She ran to the door in her shirt and saw the 11 men. Crokat grabbed at one man and asked about the explosion, receiving no answer. John Petcarne, a surgeon who lived in the same street heard nothing, but was summoned to attend Francis Busso, an Italian servant of Queen Mary.

Later, James Melville of Halhill

Sir James Melville (1535–1617) was a Scottish diplomat and memoir writer, and father of the poet Elizabeth Melville.

Life

Melville was the third son of Sir John Melville, laird of Raith, in the county of Fife, who was executed for treason ...

wrote in his ''Memoirs'' that a page said Darnley was taken out of the house before the explosion and was choked to death in a stable with a serviette in his mouth, then left under a tree. Melville went to Holyroodhouse

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly referred to as Holyrood Palace or Holyroodhouse, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinburgh ...

the next day and spoke to the Earl of Bothwell, who told him that thunder or a flash had come out of the sky, saying " souder came out of the luft", and burnt the house and there was "not a hurt nor a mark" on the body. Melville said that the royal servant Alexander Durham

Alexander Durham (died 1584) was a Scottish courtier and administrator.

His appointments included, clerk in the Exchequer, administrator of John Stewart of Coldingham, and Master of the Wardrobe to King James VI. He was also known as "Sandy Durha ...

(of Duntarvie) kept the body and stopped him seeing it.

On 12 February the Privy Council issued a proclamation that the first to reveal the names of the conspirators and participants in the murder would be pardoned, if they were involved, and have a reward of £2,000.

Aftermath

Holyrood Palace

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly referred to as Holyrood Palace or Holyroodhouse, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinbu ...

to hang her bed with black curtains for mourning and light candles in the "ruelle", a space between the bed and the wall. A lady in waiting, Madame de Bryant gave him a fried egg for his breakfast. He noticed her speaking privately with James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell

James Hepburn, 1st Duke of Orkney and 4th Earl of Bothwell ( – 14 April 1578), better known simply as Lord Bothwell, was a prominent Scottish nobleman. He was known for his marriage to Mary, Queen of Scots, as her third and final husband ...

, concealed behind a curtain.

Suspicion was placed upon Queen Mary and the Earl of Bothwell. Although Bothwell was accused of being the lead conspirator in Lord Darnley's murder by Lord Lennox, he was found not guilty in April 1567 by the Privy council of Scotland

The Privy Council of Scotland ( — 1 May 1708) was a body that advised the Scottish monarch. In the range of its functions the council was often more important than the Estates in the running the country. Its registers include a wide range of m ...

. After his acquittal, Bothwell made his supporters sign a pledge called the Ainslie Tavern Bond

The Ainslie Tavern Bond (also known as the "Ainslie Band", or the "Ainslie Tavern Band") was a document signed on about 20 April 1567 by a number of Scottish bishops and nobles. The bond approved the James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, Earl of ...

. Queen Mary married Bothwell the following month, three months after Darnley's murder. In her letters, Queen Mary defended her choice of husband, stating that she felt that she and the country were in danger and that Lord Bothwell was proven both in battle and as a defender of Scotland: "...the true occasions which has moved us to take the Duke of Orkney othwellto husband..."

Bothwell's enemies, called the Confederate Lords, gained control of Edinburgh and captured the Queen at the battle of Carberry Hill

The Battle of Carberry Hill took place on 15 June 1567, near Musselburgh, East Lothian, a few miles east of Edinburgh, Scotland. A number of Scottish lords objected to the rule of Mary, Queen of Scots, after she had married the Earl of Bothwell, ...

. The Confederate Lords said that their disapproval of the marriage to Bothwell was the cause of their rebellion. Bothwell escaped and sailed to Shetland and then Norway. Four of his men who were already in prison were tortured on 26 June 1567, being "put in the irnis ronsand turmentis, for furthering the tryall of the veritie." The Privy Council, led by the Earl of Morton

The title Earl of Morton was created in the Peerage of Scotland in 1458 for James Douglas of Dalkeith. Along with it, the title Lord Aberdour was granted. This latter title is the courtesy title for the eldest son and heir to the Earl of Morto ...

, noted this application of torture was a special case, and the method was not to be used in other cases. Mary was imprisoned at Loch Leven Castle

Lochleven Castle is a ruined castle on an island in Loch Leven, in the Perth and Kinross local authority area of Scotland. Possibly built around 1300, the castle was the site of military action during the Wars of Scottish Independence (1296� ...

and persuaded to abdicate

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

.

Darnley's death remains one of the great unsolved historical mysteries, compounded by the controversial Casket letters

The Casket letters were eight letters and some sonnets said to have been written by Mary, Queen of Scots, to the Earl of Bothwell, between January and April 1567. They were produced as evidence against Queen Mary by the Scottish lords who opposed ...

which were alleged to incriminate Queen Mary in the plot to murder her husband, while Mary's half-brother, James Stewart, Earl of Moray

James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray (c. 1531 – 23 January 1570) was a member of the House of Stewart as the illegitimate son of King James V of Scotland. A supporter of his half-sister Mary, Queen of Scots, he was the regent of Scotland for his ...

, who became Regent of Scotland

A regent is a person selected to act as head of state (ruling or not) because minority reign, the ruler is a minor, not present, or debilitated. Currently there is only one ruling Regency (government), Regency in the world, sovereign Liechtens ...

after Mary's abdication, is reputed to have signed a bond at Craigmillar Castle

Craigmillar Castle is a ruined medieval castle in Edinburgh, Scotland. It is south-east of the city centre, on a low hill to the south of the modern suburb of Craigmillar. The Preston family of Craigmillar, the local feudal barons, began build ...

with other Lords in December 1566 pledging to dispose of Darnley.

Trials and convictions

Records of the subsequent trials with statements from the accused and witnesses are an important source of information on the events of February 1567. Most were published in Pitcairn's ''Ancient Criminal Trials in Scotland'' and

Records of the subsequent trials with statements from the accused and witnesses are an important source of information on the events of February 1567. Most were published in Pitcairn's ''Ancient Criminal Trials in Scotland'' and Malcolm Laing

Malcolm Laing (1762 – 6 November 1818) was a Scottish historian, advocate and politician.

Life

He was born to Robert Laing and Barbara Blaw at the paternal estate of Strynzia or Strenzie, on Stronsay, Orkney; Samuel Laing and Gilbert Laing ...

's ''History of Scotland.'' The accused were interrogated after Mary's abdication. Alternative theories of the murder have to disregard their evidence. Captain William Blackadder, an associate of Bothwell, was one of the first to be executed on 14 June 1567, although it was said he was only a bystander. Lord Herries wrote in 1656 that Blackadder rushed out of a tavern at the Tron on the Royal Mile

The Royal Mile () is a succession of streets forming the main thoroughfare of the Old Town of the city of Edinburgh in Scotland. The term was first used descriptively in W. M. Gilbert's ''Edinburgh in the Nineteenth Century'' (1901), des ...

at the sound of the explosion and was arrested. He swore he was innocent before an assize made of Lennox men, tenants of Darnley's father, and was hanged, drawn and quartered. In December 1567, John Hepburn of Boltoun (John of Bowtoun), John Hay heir apparent of Tallo, William Powrie and George Dalgleish, all servants of Bothwell, were put on trial. They were condemned to be hanged and quartered. The head of Dalgleish, who had delivered the casket letters to the Earl of Morton

The title Earl of Morton was created in the Peerage of Scotland in 1458 for James Douglas of Dalkeith. Along with it, the title Lord Aberdour was granted. This latter title is the courtesy title for the eldest son and heir to the Earl of Morto ...

, was set on the Netherbow gate of Edinburgh.

William Powrie had made a statement in June, which describes how he and his companions carried the powder to the King's Lodging. He included the detail that as they were carrying the empty chests back up Blackfriar's Wynd, they saw the Queen and her party, "going before thame with lit torches." Thomas Nelson, a servant in Darnley's bedchamber noted that it was first thought they would go to stay at Craigmillar Castle, then the Duke's Lodging at Kirk o'Field. When they arrived at the Provost's Lodging, Mary made her servant Servais de Condé Servais de Condé or Condez (employed 1561-1574) was a French servant at the court of Mary Queen of Scots, in charge of her wardrobe and the costumes for masques performed at court.

Varlet of the Wardrobe

He was usually referred to as Servais or ...

provide hangings for the chamber and a new black velvet bed. Robert Balfour, the owner, gave Nelson the keys, except those of the door in the cellar which exited south through the town wall. After a couple of nights the Queen had the black bed replaced with an old purple one, because bath water might spoil the new bed, and she put a green bed for herself in a lower (laich) chamber. George Buchanan

George Buchanan ( gd, Seòras Bochanan; February 1506 – 28 September 1582) was a Scottish historian and humanist scholar. According to historian Keith Brown, Buchanan was "the most profound intellectual sixteenth century Scotland produced." ...

argued in his ''History of Scotland'' published in 1582, that this substitution for the new bed proved Mary's involvement in the murder.

The French valet, Nicolas Hubert, called Paris, said that Bothwell came to the lodging with Mary, and making the excuse that he needed the toilet, took Paris aside and asked him for the keys. Paris explained that it was not his role to hold the keys. Bothwell told him of his plans. Paris was troubled by the conversation, and went to pace up and down in St Giles Kirk. Fearful of the conspiracy he considered taking ship at Leith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by '' Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

. In his second interrogation Paris named Captain Blackadder, who had already been executed. Paris was executed on 16 August 1567.

Some conspiracy theories

One longstanding theory is the suggestion that the Earls of Morton and Moray were behind the murder, directing Bothwell's actions, to forward Moray's ambitions. These Earls made a denial of their involvement in their lifetime. The later and partisan ''Memoirs'' written by John Maxwell, Lord Herries in 1656, follow and develop this line of reasoning. Herries, after considering the arguments of previous writers, believed that Mary herself was innocent of involvement, and the two Earls arranged her marriage to Bothwell. After the explosion, SirWilliam Drury

Sir William Drury (2 October 152713 October 1579) was an English statesman and soldier.

Family

William Drury, born at Hawstead in Suffolk on 2 October 1527, was the third son of Sir Robert Drury (c. 1503–1577) of Hedgerley, Buckinghamshi ...

reported to the English Secretary of State William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley

William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley (13 September 15204 August 1598) was an English statesman, the chief adviser of Queen Elizabeth I for most of her reign, twice Secretary of State (1550–1553 and 1558–1572) and Lord High Treasurer from 1 ...

, that James Balfour had purchased gunpowder worth 60 pounds Scots shortly beforehand. Balfour could have stored the powder at the property next-door, also owned by the Balfours, and then mined the prince's lodgings by moving the powder from one cellar to the next. However, this James Balfour was the captain of Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle is a historic castle in Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland. It stands on Castle Rock (Edinburgh), Castle Rock, which has been occupied by humans since at least the Iron Age, although the nature of the early settlement is unclear. ...

and was likely to buy powder for use at the Castle.

The home of James Hamilton, Duke of Châtellerault

James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Châtellerault, 2nd Earl of Arran ( 1519 – 22 January 1575), was a Scottish nobleman and head of the House of Hamilton. A great-grandson of King James II of Scotland, he was heir presumptive to the Scottish thron ...

, lay in the same quadrangle, and Hamilton was an old enemy of Darnley's family, as they had competing claims in the line of succession to the Scottish throne. Hamilton was also related to the Douglas family

Douglas may refer to:

People

* Douglas (given name)

* Douglas (surname)

Animals

*Douglas (parrot), macaw that starred as the parrot ''Rosalinda'' in Pippi Longstocking

* Douglas the camel, a camel in the Confederate Army in the American Civil ...

, who were no friends of Darnley either. There is no shortage of suspects, and the full facts of the murder have never been deduced.

Sketches sent to England

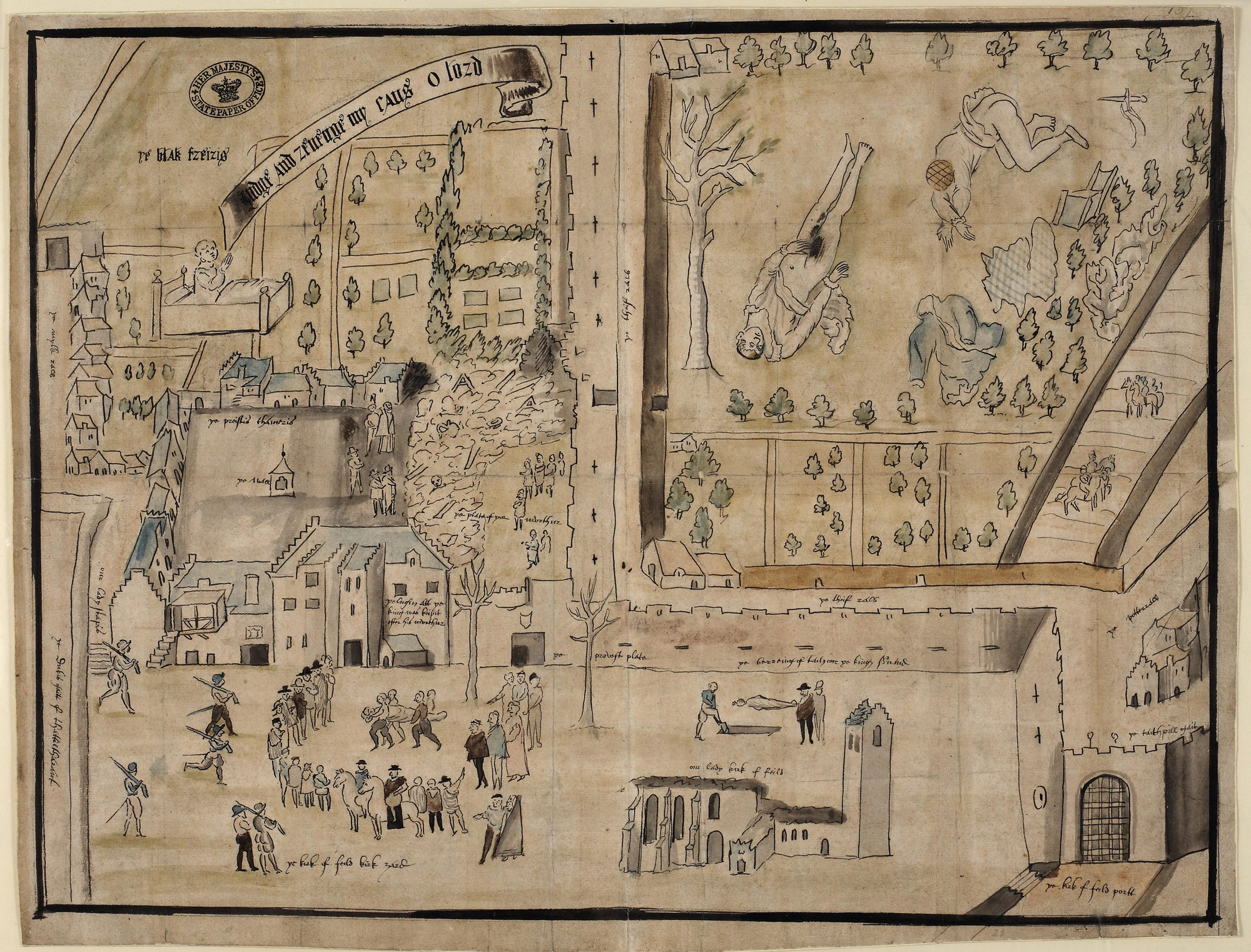

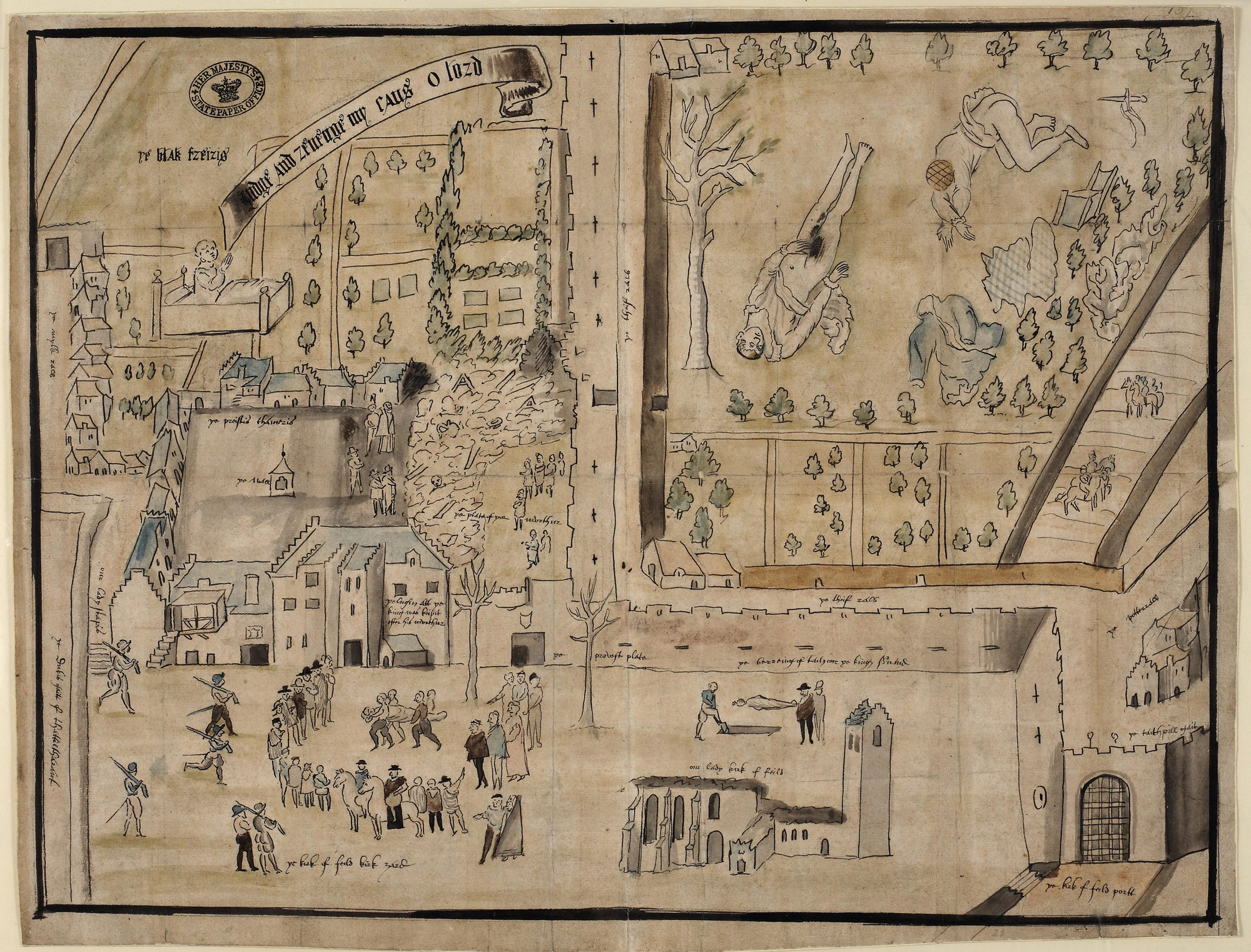

A contemporary drawing of the murder scene at Kirk o' Field includes at the top left the infantJames VI

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

sitting up in his cot praying: "Judge and avenge my cause, O Lord;" in the centre lie the rubble remains of the house; to the right Darnley and his servant lie dead in the orchard; below, the townspeople of Edinburgh gather round and four soldiers remove a body for burial. The artist was employed by Sir William Drury

Sir William Drury (2 October 152713 October 1579) was an English statesman and soldier.

Family

William Drury, born at Hawstead in Suffolk on 2 October 1527, was the third son of Sir Robert Drury (c. 1503–1577) of Hedgerley, Buckinghamshi ...

, Marshall of Berwick, who sent the sketch to England.

The murder scene sketch has been dated 9 February 1567 (in error). The sketch includes several cryptic elements. At first it appears to be an eye-witness account of the murder scene. However the infant James was not present, nor could he speak the words attributed to him at the time. Thus the image changes by its inclusion from an eye-witness account, to a propaganda poster, as an allegory. This same motto and a similar image of father and son was used on the banner of the rebel Confederate Lords, first displayed at Edinburgh castle

Edinburgh Castle is a historic castle in Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland. It stands on Castle Rock (Edinburgh), Castle Rock, which has been occupied by humans since at least the Iron Age, although the nature of the early settlement is unclear. ...

, then at the battle of Carberry Hill

The Battle of Carberry Hill took place on 15 June 1567, near Musselburgh, East Lothian, a few miles east of Edinburgh, Scotland. A number of Scottish lords objected to the rule of Mary, Queen of Scots, after she had married the Earl of Bothwell, ...

. This banner was described by the French ambassador, Philibert du Croc, and a sketch of the banner was also sent to England. It shows the town wall and the open door to the lodging (mentioned in Thomas Nelson's statement) in the background. A mystery in the Kirk o' Field plan may be the image of the mounted riders in the far right picture. Some riders at night were mentioned a week later as being a band of men led by Andrew Kerr who were present the night of the murder. It is unclear how the artist drawing the scene the following day knew to include the image of these night riders, if such they are, not known to be present until a week later.

A placard was created and distributed throughout Edinburgh which portrayed Mary as a seductive mermaid. The author of the mermaid placard was never identified, and again a copy was sent to England.''Calendar of State Papers Foreign, Elizabeth'', vol. 8: 1566–1568 (1871), pp. 241–252: picture in Loades, David, ''Elizabeth I'', National Archives, (2003), 73

References

Further reading

*George Buchanan

George Buchanan ( gd, Seòras Bochanan; February 1506 – 28 September 1582) was a Scottish historian and humanist scholar. According to historian Keith Brown, Buchanan was "the most profound intellectual sixteenth century Scotland produced." ...

''Ane Detectioun of the Duings of Marie Quene of Scottes, touchand the murder of hir husband'', (1571)

from

University of Birmingham

, mottoeng = Through efforts to heights

, established = 1825 – Birmingham School of Medicine and Surgery1836 – Birmingham Royal School of Medicine and Surgery1843 – Queen's College1875 – Mason Science College1898 – Mason Univers ...

Philological Museum

Pitcairn, Robert, ed., ''Criminal Trials in Scotland'', vol.1 part 2, (1833)

pp. 488–513, original confessions of accessories

Laing, Malcolm, ''History of Scotland with a Preliminary Dissertation on the Participation of Mary, Queen of Scots, in the Murder of Darnley'', vol. 2 (1819)

includes the confessions, the casket letters, and other relevant documents. * * * * * * {{coord, 55.9456, -3.1811, type:landmark_region:GB, display=title Murder in Edinburgh 1567 in Scotland History of Edinburgh Political scandals in Scotland Mary, Queen of Scots Murder in 1567